Powered by Camelot Media Ltd

Dauntsey Wharf Invoice - 1860

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page Four

Using & Working the Canal -

The Communities

Regular services

By the time work on the Kennet and Avon Canal was completed, both the Kennet and the Avon Navigations had long histories of use, and trade had continued on these waterways for many years.

It therefore followed that as the new waterway gradually reached completion, the knowledge, skills, working practices and social arrangements associated with the original navigations, spread to significantly influence the canal and its operational environment.

Once the canal was operational, long distance trade between London, Bristol, and the inland towns between, soon developed.

Families

Regular services were provided by some carriers from Bristol to major London wharves such as those at Queenhithe Dock, Kennet Wharf, and Three Cranes Wharf, all close to Southwark Bridge.

Apart from these regular services, there were additional special transport contracts.

For example in 1812 the marble plinths for Lord Pembroke's new colonnade at Wilton House near Salisbury were delivered by barge from London to Devizes.

Compared with travel by road, the regular canal service was considered to be exceedingly fast, with duplicate crews working all day and through the night, and regular changes of horses being arranged at suitable locations along the canal. Eventually these arrangements enabled a five-day delivery service between the two cities to be established.

A vast improvement on the long, dangerous, and uncertain travel a coastal voyage would entail.

Skills

The elder Hams, Tom's father, earned 12 shillings (60p) a week as master of the Kennet Barge Unity.

This amount was below the national average for barge work at the time, but if a barge master did not have to pay for his crew or stabling for the horse, and had housing provided, then it could well have been a reasonable income.

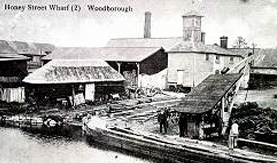

Honeystreet was an important trading point on the K&A with virtually the whole village owned by Robbins Lane and Pinniger, who provided housing for their workers.

This sort of arrangement was not uncommon at the time, and with such stability it is not surprising that little migration occurred, and that rural families often remained in one area for many generations.

Crews

Many of the boats used were individually owned, with the owner and his immediate family living aboard in what was likely to be their only accommodation.

This arrangement enabled family members, including children, to undertake crewing duties, and as the work was invariably unpaid, costs could be kept down and hopefully, profits and income for the family increased.

Earnings

In 1844 the canal company ruled that each barge or pair of boats working "fly" (fast service with navigational priority) must be crewed by a captain and four men and that each single boat had to be crewed by a master and three men.

Museum records show that Tom Hams and his father, George, both worked as bargemen for Robins, Lane and Pinniger, a local company established in 1812 as boat builders, traders and sawmill owners at Honeystreet in Wiltshire.

Trades

In addition to barge and boat owners and their families, canal operations required many other trades and skills for its successful operation.

These included maintenance and other engineers, boat builders, carpenters, blacksmiths, toll clerks and agents, as well as wharfingers, masons, lock keepers, and labourers.

As an example of this, the canal company employed the following staff in 1823.

Some of these were provided with the remuneration shown:

• One engineer - £300 pa plus house

• One sub engineer & mason - £100 pa

• Thirty-one lock keepers - 10/6 (52 ½ p) per week plus house

• Twenty-six navigators

• Twelve carpenters

• Two pump men

• One blacksmith

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Using & Working the Canal -

The Cargoes

Local trade

Whilst the canal had been built primarily to link the ports of Bristol and London, a proportion of the trade was more local.

Tolls

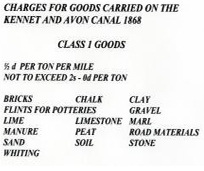

The Company charged tolls on goods carried at so many pence per mile and for this purpose goods were divided into 4 classes, each carrying a different charge.

This list (right) indicates the diversity of cargoes carried.

In order to properly administer the toll system, the company arranged for all canal craft carrying cargoes to be gauged at special docks.

This procedure involved measuring the freeboard, or dry inches, with a toll staff. Weights were added to the boat in ¼ ton or ½ ton stages.

In this way a toll collector could determine the weight carried by a narrow boat or barge of any size and capacity.

Tributary canals

At approximately the same time as the Kennet and Avon Canal became operational, the Somerset Coal Canal and the Wilts and Berks Canal were also completed.

Coal from the Somerset coalfields was brought down the coal canal to join the K&A at Brassknocker Basin at the western end of the Dundas Aqueduct.

From this junction coal could be taken anywhere on the Kennet and Avon, and soon became an important cargo.

The Wilts and Berks Canal ran from Semington, near Melksham, Wiltshire, to the Thames at Abingdon, Oxfordshire, and was used as a short cut for trade between the Midlands and the western end of the K&A.

These tributary canals whilst being important in their own right, also provided an added advantage in that they allowed an increase in markets for the products of those traders that used the K&A.

Cargoes

Whilst cargoes were often diverse in nature, George Hams spent much of his working life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries carrying tin plate boxes from Robbins Lane & Pinniger to Bristol, on the barge 'Unity', returning from Avonmouth near Bristol with deal boards and scantlings.A trip to Avonmouth or to London with a horse drawn barge was not an easy journey.The canal company which, by then, was the GWR, did not allow steam powered vessels to trade on the waterway as they claimed that such craft caused bank wash and increased the cost of maintenance as more frequent dredging became necessary as a result. As a consequence horse, or some times manpower, was the only motive force available, particularly as sails were normally impracticable within the confines of a canal.

Alec Huntly who lived beside the canal at Honeystreet remembered seeing timber stamped with exotic sounding names such as Archangel, Murmansk, Bergen and Oslo being delivered to Robbins Lane and Pinnegar's wharves.

That company also ran a fertiliser factory at Honeystreet, near Pewsey in Wiltshire and Tom Hams, who worked as a bargeman at Honeystreet, for example, used to take the barge Unity to Avonmouth to pick up carboys of acid using two horses to haul the laden barge back up the Avon and on to Honeystreet.This journey was made necessary because the canal owners (GWR) considered the cargo too hazardous to transport by rail.

Only one horse was needed to return the empty carboys, so two days after the barge departed from Honeystreet the second horse, which was needed for the long haul back, would be walked to the station at Woodborough, near Pewsey to catch the train for Bristol and so meet up with the barge again.

Using & Working the Canal -

The Communities

Regular services

By the time work on the Kennet and Avon Canal was completed, both the Kennet and the Avon Navigations had long histories of use, and trade had continued on these waterways for many years.

It therefore followed that as the new waterway gradually reached completion, the knowledge, skills, working practices and social arrangements associated with the original navigations, spread to significantly influence the canal and its operational environment.

Once the canal was operational, long distance trade between London, Bristol, and the inland towns between, soon developed.

Families

Regular services were provided by some carriers from Bristol to major London wharves such as those at Queenhithe Dock, Kennet Wharf, and Three Cranes Wharf, all close to Southwark Bridge.

Apart from these regular services, there were additional special transport contracts.

For example in 1812 the marble plinths for Lord Pembroke's new colonnade at Wilton House near Salisbury were delivered by barge from London to Devizes.

Compared with travel by road, the regular canal service was considered to be exceedingly fast, with duplicate crews working all day and through the night, and regular changes of horses being arranged at suitable locations along the canal. Eventually these arrangements enabled a five-day delivery service between the two cities to be established.

A vast improvement on the long, dangerous, and uncertain travel a coastal voyage would entail.

Skills

The elder Hams, Tom's father, earned 12 shillings (60p) a week as master of the Kennet Barge Unity.

This amount was below the national average for barge work at the time, but if a barge master did not have to pay for his crew or stabling for the horse, and had housing provided, then it could well have been a reasonable income.

Honeystreet was an important trading point on the K&A with virtually the whole village owned by Robbins Lane and Pinniger, who provided housing for their workers.

This sort of arrangement was not uncommon at the time, and with such stability it is not surprising that little migration occurred, and that rural families often remained in one area for many generations.

Crews

Many of the boats used were individually owned, with the owner and his immediate family living aboard in what was likely to be their only accommodation.

This arrangement enabled family members, including children, to undertake crewing duties, and as the work was invariably unpaid, costs could be kept down and hopefully, profits and income for the family increased.

Earnings

In 1844 the canal company ruled that each barge or pair of boats working "fly" (fast service with navigational priority) must be crewed by a captain and four men and that each single boat had to be crewed by a master and three men.

Museum records show that Tom Hams and his father, George, both worked as bargemen for Robins, Lane and Pinniger, a local company established in 1812 as boat builders, traders and sawmill owners at Honeystreet in Wiltshire.

Trades

In addition to barge and boat owners and their families, canal operations required many other trades and skills for its successful operation.

These included maintenance and other engineers, boat builders, carpenters, blacksmiths, toll clerks and agents, as well as wharfingers, masons, lock keepers, and labourers.

As an example of this, the canal company employed the following staff in 1823.

Some of these were provided with the remuneration shown:

• One engineer - £300 pa plus house

• One sub engineer & mason - £100 pa

• Thirty-one lock keepers - 10/6 (52 ½ p) per week plus house

• Twenty-six navigators

• Twelve carpenters

• Two pump men

• One blacksmith

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Using & Working the Canal -

The Cargoes

Local trade

Whilst the canal had been built primarily to link the ports of Bristol and London, a proportion of the trade was more local.

Tolls

The Company charged tolls on goods carried at so many pence per mile and for this purpose goods were divided into 4 classes, each carrying a different charge.

This list (right) indicates the diversity of cargoes carried.

In order to properly administer the toll system, the company arranged for all canal craft carrying cargoes to be gauged at special docks.

This procedure involved measuring the freeboard, or dry inches, with a toll staff. Weights were added to the boat in ¼ ton or ½ ton stages.

In this way a toll collector could determine the weight carried by a narrow boat or barge of any size and capacity.

Tributary canals

At approximately the same time as the Kennet and Avon Canal became operational, the Somerset Coal Canal and the Wilts and Berks Canal were also completed.

Coal from the Somerset coalfields was brought down the coal canal to join the K&A at Brassknocker Basin at the western end of the Dundas Aqueduct.

From this junction coal could be taken anywhere on the Kennet and Avon, and soon became an important cargo.

The Wilts and Berks Canal ran from Semington, near Melksham, Wiltshire, to the Thames at Abingdon, Oxfordshire, and was used as a short cut for trade between the Midlands and the western end of the K&A.

These tributary canals whilst being important in their own right, also provided an added advantage in that they allowed an increase in markets for the products of those traders that used the K&A.

Cargoes

Whilst cargoes were often diverse in nature, George Hams spent much of his working life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries carrying tin plate boxes from Robbins Lane & Pinniger to Bristol, on the barge 'Unity', returning from Avonmouth near Bristol with deal boards and scantlings.A trip to Avonmouth or to London with a horse drawn barge was not an easy journey.The canal company which, by then, was the GWR, did not allow steam powered vessels to trade on the waterway as they claimed that such craft caused bank wash and increased the cost of maintenance as more frequent dredging became necessary as a result. As a consequence horse, or some times manpower, was the only motive force available, particularly as sails were normally impracticable within the confines of a canal.

Alec Huntly who lived beside the canal at Honeystreet remembered seeing timber stamped with exotic sounding names such as Archangel, Murmansk, Bergen and Oslo being delivered to Robbins Lane and Pinnegar's wharves.

That company also ran a fertiliser factory at Honeystreet, near Pewsey in Wiltshire and Tom Hams, who worked as a bargeman at Honeystreet, for example, used to take the barge Unity to Avonmouth to pick up carboys of acid using two horses to haul the laden barge back up the Avon and on to Honeystreet.This journey was made necessary because the canal owners (GWR) considered the cargo too hazardous to transport by rail.

Only one horse was needed to return the empty carboys, so two days after the barge departed from Honeystreet the second horse, which was needed for the long haul back, would be walked to the station at Woodborough, near Pewsey to catch the train for Bristol and so meet up with the barge again.

Somerset Coal Canal Permit

Narrowboat 'Caroline'

Honeystreet Wharf, Woodborough, Wiltshire

1868 Canal Charges

Toll staff

Copyright the Kennet & Avon Trade Association MMXII

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sponsored by the Kennet & Avon Trade Association