Powered by Camelot Media Ltd

Dundas Aqueduct

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Page Three

Building the Canal - Building Methods,

their problems & Solutions

Surveyors

John Rennie and the committee of management appointed different surveyors at various times to survey the possible and chosen routes.

Each surveyor did this either on foot or on horseback, making measurements and calculations for every mile travelled.

At its western end the building route passed through hilly country and the only way the canal could be constructed at this point was to use the same contour level either side of the river Avon, and build aqueducts which twice carried the canal across the river valley from one side to the other.

This pioneering work established a base line from which the later railway builders could further develop arrangements for constructing similar structures.

Cutting the channel

Picks and shovels together with wheelbarrows for removing waste, were the main tools for digging the channel.

However in deep cuttings, arrangements for dragging men with their barrows up the sides of the cut using horse-powered winches were developed.

Railway builders subsequently used these later methods when the railway system was being constructed.

Tunnels

Tunnels posed particular problems that frequently elicited simple but effective solutions.

The route of a tunnel for example, would be surveyed across the top of the ground and at fixed points the rise would be calculated from the measured elevation.

Sinking shafts at these points to a depth of the calculated rise, would then produce a level for the tunnellers.

Direction for the tunneling work would be taken from plumb lines lowered into the shafts, and these vertical lines would be positioned at the surface to correspond with the surveyed direction.

The plumb lines thus gave the direction at the bottom of the shaft and the result would be a straight tunnel in the right direction.

Avoiding water loss

To minimise water loss the canal channel was lined with clay, usually to a depth of 3 feet (approximately 1 metre).

The hard, quarried clay was broken into lumps, spread in the channel and wetted.

Cattle would then be driven over the clay so that it was "puddled" into a malleable consistency, which allowed it to be more readily used.

Aqueducts and bridges

In addition to aqueducts, 111 bridges were built, mostly of stone at the western end and of brick, east of Devizes where locally quarried stone was less plentiful or suitable.

Where aqueduct building in particular was concerned some vested interests had to be accommodated.

The original plan was to build the two Avon valley aqueducts of brick.

However the united voice of canal company shareholders who also had interests in stone quarries, forced John Rennie to build these structures of stone.

Whilst the large aqueducts were major engineering projects, the smaller bridges that allowed access over the canal, were simpler to build.

These were often constructed on a timber frame that was removed after completion of the building work.

Keeping a level course

Early canals followed a single contour as much as possible to reduce the number of locks but this led to some strange meandering routes.

By the time that the Kennet and Avon Canal was built a "cut and fill" technique had become the accepted method for maintaining a level.

Using this technique a cutting would be made through high ground and the spoil used to build an embankment across lower lying terrain.

In practice though the canal builders needed to be flexible, and former methods were sometimes still used if considered appropriate at the time.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Working the Canal - The Boats & Barges

Types of craft

Narrow boats and Kennet barges were the primary craft used on the Kennet and Avon Canal.The canal company specified that these had to be of the following dimensions:

• Approved barge (Class A) - 69 feet (21m) long x 5 feet

(1.5m) deep x 12ft 4ins (3.8m) beam, with a capacity of

60 tons.

• Approved boat (Class A) - 69 feet long x 4 feet (1.2m)

deep x 6 ft 11ins (2.1m)beam with a capacity of 35 tons.

• Non - approved vessels (Class B) - to the maximum

dimensions of 69 feet long x 5 feet deep x 14 feet (4.3m)

beam, with a capacity of 70 tons.

The company also approved a boat it called the mule boat (wide boat).This had the same dimensions as the approved barge except that the beam was 10 feet (3m) giving it a capacity of approximately 50 tons.

While the cabin of the barge was below the rear deck with access by a companionway, the mule by comparison had the appearance of an over wide narrow boat.

Larger boats

These criteria aside, larger barges were sometimes built, particularly for use on the Avon Navigation. One such vessel was the 'Harriett' which was built in 1894 by Robbins Lane and Pinniger, for Ashmeads of Bristol.This barge was over 70 foot long with a beam that was slightly over 14 feet.

On her delivery voyage from Honeystreet to Bristol, 'Harriett' stuck fast in a lock at Foxhangers near Devizes.

In order to continue their passage, the delivery crew chipped away portions of the wooden quoins and brickwork in the lock sides causing a great deal of damage.

Surprisingly, the canal company took no action against Robbins Lane and Pinniger for the damage caused, simply letting them off with a caution.

It is likely that this was because the firm had grounds for complaint against the canal company on another matter and, that some tit-for-tat private resolution was reached as a consequence.

Boat building

Narrow boats and barges were built in their greatest numbers at Newbury in Berkshire and Honeystreet in Wiltshire.

Robbins Lane and Pinniger of Honeystreet also built spoon dredgers for K&A use, sailing trows for the river Severn and large barges for use on the river Wey.

The last trading vessel built by the company, was the barge 'Unity', which was built in 1896 and which continued in use until 1933.

Some of the companies most well known barges were built in the early 20th century for the United Alkali Company (later ICI). These were all named after precious stones and collectively known as the stone barges.

Steam dredging

Steam dredgers for use on the canal, were built by Stothert and Pitt at Bath.

These were commissioned by the Great Western Railway (GWR) who, by that time, owned the canal.

Remains of 'Harriett'

Although a number of working narrow boats still remain, all the Kennet barges have long disappeared.

That is apart from one, because the remains of 'Harriett' can still be seen on the banks of the river Severn at Purton, where in the mid 1960's she was taken to be hulked, and is now named as a scheduled monument.

Although ravaged by neglect and the elements, the shape and form of the old barge is still very evident and many of her oak timbers are as solid as the day they were fitted nearly 110 years ago.

Building the Canal - Building Methods,

their problems & Solutions

Surveyors

John Rennie and the committee of management appointed different surveyors at various times to survey the possible and chosen routes.

Each surveyor did this either on foot or on horseback, making measurements and calculations for every mile travelled.

At its western end the building route passed through hilly country and the only way the canal could be constructed at this point was to use the same contour level either side of the river Avon, and build aqueducts which twice carried the canal across the river valley from one side to the other.

This pioneering work established a base line from which the later railway builders could further develop arrangements for constructing similar structures.

Cutting the channel

Picks and shovels together with wheelbarrows for removing waste, were the main tools for digging the channel.

However in deep cuttings, arrangements for dragging men with their barrows up the sides of the cut using horse-powered winches were developed.

Railway builders subsequently used these later methods when the railway system was being constructed.

Tunnels

Tunnels posed particular problems that frequently elicited simple but effective solutions.

The route of a tunnel for example, would be surveyed across the top of the ground and at fixed points the rise would be calculated from the measured elevation.

Sinking shafts at these points to a depth of the calculated rise, would then produce a level for the tunnellers.

Direction for the tunneling work would be taken from plumb lines lowered into the shafts, and these vertical lines would be positioned at the surface to correspond with the surveyed direction.

The plumb lines thus gave the direction at the bottom of the shaft and the result would be a straight tunnel in the right direction.

Avoiding water loss

To minimise water loss the canal channel was lined with clay, usually to a depth of 3 feet (approximately 1 metre).

The hard, quarried clay was broken into lumps, spread in the channel and wetted.

Cattle would then be driven over the clay so that it was "puddled" into a malleable consistency, which allowed it to be more readily used.

Aqueducts and bridges

In addition to aqueducts, 111 bridges were built, mostly of stone at the western end and of brick, east of Devizes where locally quarried stone was less plentiful or suitable.

Where aqueduct building in particular was concerned some vested interests had to be accommodated.

The original plan was to build the two Avon valley aqueducts of brick.

However the united voice of canal company shareholders who also had interests in stone quarries, forced John Rennie to build these structures of stone.

Whilst the large aqueducts were major engineering projects, the smaller bridges that allowed access over the canal, were simpler to build.

These were often constructed on a timber frame that was removed after completion of the building work.

Keeping a level course

Early canals followed a single contour as much as possible to reduce the number of locks but this led to some strange meandering routes.

By the time that the Kennet and Avon Canal was built a "cut and fill" technique had become the accepted method for maintaining a level.

Using this technique a cutting would be made through high ground and the spoil used to build an embankment across lower lying terrain.

In practice though the canal builders needed to be flexible, and former methods were sometimes still used if considered appropriate at the time.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Working the Canal - The Boats & Barges

Types of craft

Narrow boats and Kennet barges were the primary craft used on the Kennet and Avon Canal.The canal company specified that these had to be of the following dimensions:

• Approved barge (Class A) - 69 feet (21m) long x 5 feet

(1.5m) deep x 12ft 4ins (3.8m) beam, with a capacity of

60 tons.

• Approved boat (Class A) - 69 feet long x 4 feet (1.2m)

deep x 6 ft 11ins (2.1m)beam with a capacity of 35 tons.

• Non - approved vessels (Class B) - to the maximum

dimensions of 69 feet long x 5 feet deep x 14 feet (4.3m)

beam, with a capacity of 70 tons.

The company also approved a boat it called the mule boat (wide boat).This had the same dimensions as the approved barge except that the beam was 10 feet (3m) giving it a capacity of approximately 50 tons.

While the cabin of the barge was below the rear deck with access by a companionway, the mule by comparison had the appearance of an over wide narrow boat.

Larger boats

These criteria aside, larger barges were sometimes built, particularly for use on the Avon Navigation. One such vessel was the 'Harriett' which was built in 1894 by Robbins Lane and Pinniger, for Ashmeads of Bristol.This barge was over 70 foot long with a beam that was slightly over 14 feet.

On her delivery voyage from Honeystreet to Bristol, 'Harriett' stuck fast in a lock at Foxhangers near Devizes.

In order to continue their passage, the delivery crew chipped away portions of the wooden quoins and brickwork in the lock sides causing a great deal of damage.

Surprisingly, the canal company took no action against Robbins Lane and Pinniger for the damage caused, simply letting them off with a caution.

It is likely that this was because the firm had grounds for complaint against the canal company on another matter and, that some tit-for-tat private resolution was reached as a consequence.

Boat building

Narrow boats and barges were built in their greatest numbers at Newbury in Berkshire and Honeystreet in Wiltshire.

Robbins Lane and Pinniger of Honeystreet also built spoon dredgers for K&A use, sailing trows for the river Severn and large barges for use on the river Wey.

The last trading vessel built by the company, was the barge 'Unity', which was built in 1896 and which continued in use until 1933.

Some of the companies most well known barges were built in the early 20th century for the United Alkali Company (later ICI). These were all named after precious stones and collectively known as the stone barges.

Steam dredging

Steam dredgers for use on the canal, were built by Stothert and Pitt at Bath.

These were commissioned by the Great Western Railway (GWR) who, by that time, owned the canal.

Remains of 'Harriett'

Although a number of working narrow boats still remain, all the Kennet barges have long disappeared.

That is apart from one, because the remains of 'Harriett' can still be seen on the banks of the river Severn at Purton, where in the mid 1960's she was taken to be hulked, and is now named as a scheduled monument.

Although ravaged by neglect and the elements, the shape and form of the old barge is still very evident and many of her oak timbers are as solid as the day they were fitted nearly 110 years ago.

Narrow boat 'Columba' at West Mill Wharf, Newbury, arriving from Middlewich, Cheshire, February 1950.

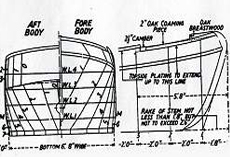

Cross section of narrowboat

Kennet barge 'Harriett' - as she is today - named as a scheduled monument.

Copyright the Kennet & Avon Trade Association MMXII

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sponsored by the Kennet & Avon Trade Association